All these snow geese overgrazed their nesting grounds. Many of these shoreline "oases" were transformed to mudflats. Comparison of the 1973 and 1996 Landsat images shows the area of bright, bare shoreline spreading inland into the vegetation, although the tidal change makes it hard to tell how much.

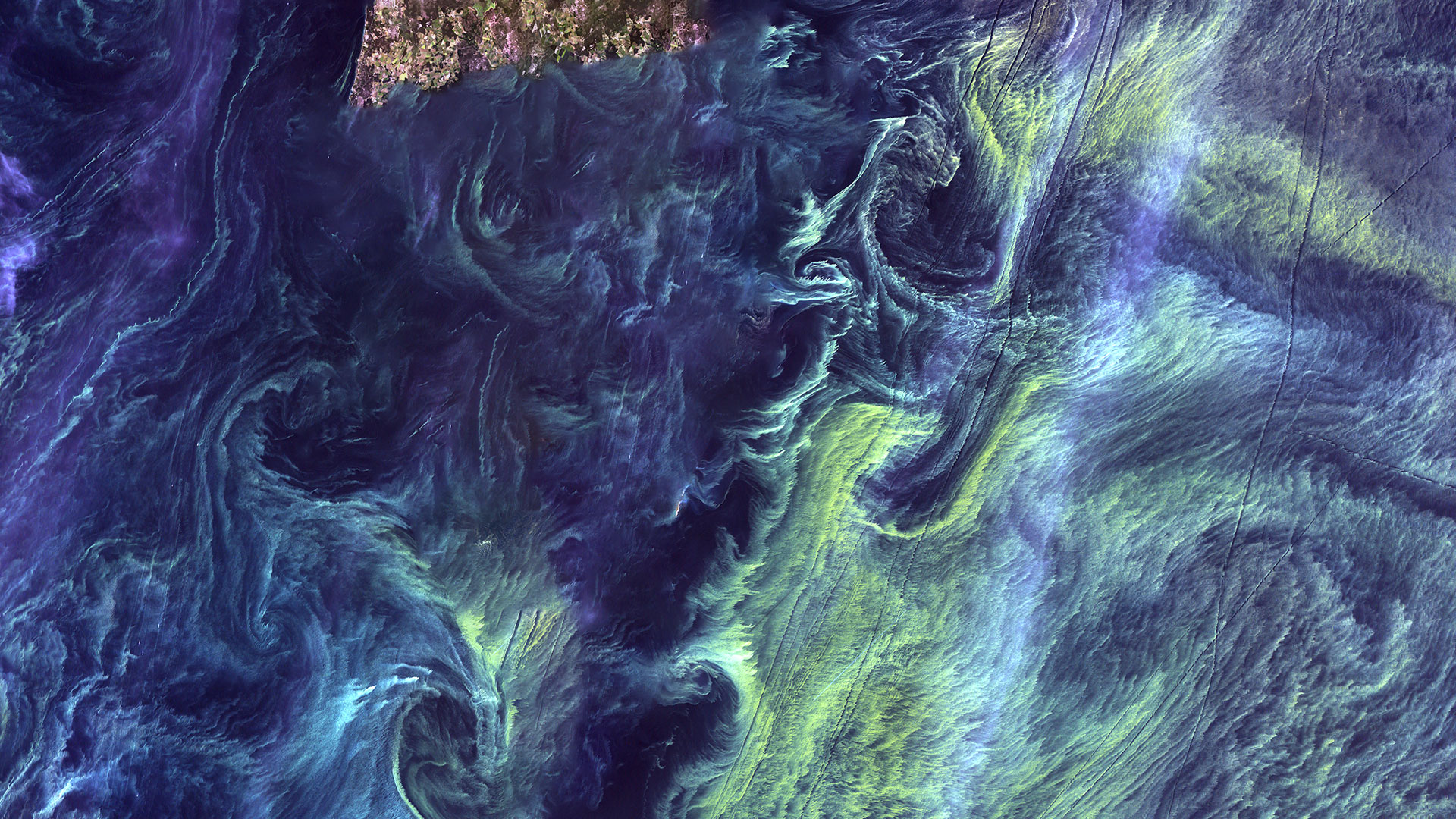

To make the changes easier to see, we simplified the Landsat images into one-dimensional "vegetation index" images, showing how much plant life there was in 1973 and 1996. Photosynthesizing plants reflect more infrared energy than visible energy; these images show that difference on a scale of –100 to +100. Green means growing plants, yellow means bare ground, and red means water (though we blacked out Hudson Bay and its inlets). Then, to make the changes even easier to see, we combined the vegetation images into a single change-image, in which green shows where vegetation increased from 1973 to 1996 and red shows where it decreased. There is a definite red swath north of the delta, inland from the beach, which indicates a sharp decrease in vegetation. The beach itself, like most of the image, shows a light yellow-green color, suggesting a slight increase in vegetative growth. This small change could be from an actual increase in vegetation, or just from sensor "noise."

Scientists evaluating 1,200 miles of shoreline habitat along Hudson Bay said about a third was severely damaged and another third destroyed. Once the soil is bare the surface temperature increases, which increases evaporation, which leaves behind an accumulation of natural salts on the surface. This salty layer inhibits the recovery of plants. Erosion also damages the thin soil. At nearby La Perouse Bay, scientists built a pen around some bared ground to keep the birds out, and after 12 years there was only 5% regrowth.

Despite the loss of forage, the geese keep homing back to the same area, and they keep reproducing using energy gained during migration. The goslings are not so lucky. Many snow goose families at La Perouse Bay walk up to 30 miles to find food, and only 10% of the goslings survive. But adults commonly live and reproduce into their teens, so the population keeps growing.

Destroyed habitat could make the aged snow goose population collapse. Already, less-numerous species have been affected; at La Perouse Bay, the numbers of American wigeons, northern shovelers, yellow rails, stilt sandpipers, Hudsonian godwits, and short-billed dowitchers have fallen 90 percent since 1980. Diseases could also sweep through the crowded snow geese, and spread to other bird species. Even if the snow geese don't collapse, the population could sink to a low level of health and productivity.

This is a new situation for wildlife managers, who worked for many years to increase population numbers. Many managers want more hunting along the migration flyways. Controlling the food supply is impossible, and reducing habitat on public lands could harm other species. It is also hard to use the nesting geese and eggs for food, since geese and people there live far apart. Government programs would be expensive to set up, and hunters already kill about a half million snow geese annually, which accounts for about two-thirds of adult snow goose mortality.

Managers have proposed removing various restrictions on hunting and even subsidies or awards for hunting. Some believe that increased hunting is "too little, too late" to prevent destruction of the habitat and collapse of the population.